Over the last 18 months I've been building a new Data and Information Access team in Defra’s Digital Data & Technology Services (DDTS) function. The team brings together data sharing and library functions and has three broad purposes, to:

- ensure that quality data and information assets are available to Defra group users

- ensure that collections, catalogues and platforms are well maintained and managed

- support the publication of Defra data and research

Maintaining catalogues of good quality metadata is critical to them all. But over the last few months I've come to realise I have a love/hate relationship with metadata and the hate is winning. But there might be some simple principles, which, if applied, could make our metadata better and our data easier to find and reuse.

Why I love metadata

I love metadata because it helps people find and share our data and information and to understand if it meets their needs.

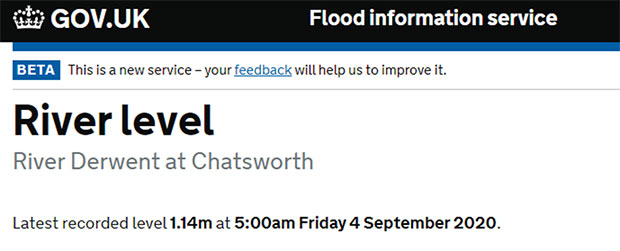

I love metadata because it helps make services work for users. For example, metadata gives users of our Flood Information Service confidence that they are looking at up-to-date information.

I also love metadata because I am a fan of a good standard (I realise this is quite geeky). There are lots of good standards in the metadata domain and these standards drive the sharing and reuse of data.

Why I hate metadata

It feels like there are too many standards, people seem to focus on complying with a standard and not the quality of the content, and everyone interprets standards differently.

Metadata is often disconnected from data, it is created in laborious, manual ways and often we aren’t great at keeping it up to date.

We have many ‘metadata catalogues’, 16 at the last count in Defra group I think. They are all different. Some assets are recorded in multiple catalogues, some are not recorded at all. But worst of all I don’t think the catalogues we have got make it easier for users to find the data and information they need!

The metadata problem is growing as we increasingly move towards greater use of real time data, for example from internet connected devices, telemetry systems and Earth Observation sensors, and as we move to online services like Office 365 which treat our information (documents, emails, tasks, and calls/messages) more like data.

It doesn’t feel like our current approaches to metadata are sustainable or working well.

The good news is that lots of work is already happening

People across government have realised there is a problem. The drive to increase the sharing of data across government means we need to be better at metadata.

There is already a lot happening in the government metadata space:

- Data Standards Authority has set a standard for metadata when sharing data across government and has started to clarify what standards should be used when

- Geospatial Commission are working hard to improve the guidance on metadata for Geospatial data through their Geospatial Data Discoverability projects and have made good recommendations on geospatial

- we are increasingly understanding the importance of making metadata ‘search engine ready’ using things like schema.org standards

- National Data Strategy Framework talks about the need to modernise the way we manage and share data across government to generate significant efficiency savings and improve services - better metadata will be critical to success

Learning to love metadata again

I’ve been thinking about how I could start to love metadata again.

It feels like a lot of the current work is focusing on what metadata we should capture and not how we should do it. Focusing on Defra’s metadata, catalogues and related processes, a lot of the pain is around how we ‘do’ metadata. We could do metadata better, resulting in improved content, quality and currency.

So I want to start a conversation about how we do metadata.

I've developed an alpha vision for metadata in Defra group and a set of principles. I'm sharing these to test them and I’d love your feedback - feel free to contribute to this collaborative document or by commenting below. If you’d like to talk to me about this work let me know via Twitter if you’d be interested joining.

Once we have an agreed vision and principles we can then start to think about the guidance, processes, and patterns that would be needed to apply them.

If this work develops into something useful, I will share the outcomes in a future post, if it doesn’t, I will try and explain why.

4 comments

Comment by Paul Geraghty posted on

The vision as such seems fine. However I'd advise to discern clearly between "machine generated data" and human input (which is where it usually/always falls down). Let me stick with your example above.

In your River Derwent example above, its extremely likely the data did not come direct from the sensor exactly like that. Someone made sure some kind of data translation was made, e.g. in the cloud somewhere, a data-head was directed to make sure the unfathomable unix-timestamp turned into 6-7-2020 not 7-6-2020, that the Lat, Lng was in Derbyshire.

These are fairly straightforward one-off tasks that require some knowledge. Once they are running right, they are always right, right? (OMG someone moved the sensor! See, I told you we should have put a gps on them.)

The problem arises when Ken in the office is tasked with summarising high level water risks to farms around Matlock which features his .xls file containing a massaged, summarised and "simplified" subset of the original data above. Ken's not sure whether he is the publisher, contributor or the author of his document, never mind what camelCase means.

These are two very distinct problems requiring two versions of "automating". The machine task simply seems to require money, an edict and ongoing quality checking. Important though Ken's summary is, its the human interjection into the data stream that causes the real problem.

Ken is not an API we cannot tweak him so easily.

Overall I'm very cynical about this, IMHO you have to simply remove that particular responsibility from humans, just the leave the decision

"Do you want to share this data? Y/N".

5 mins later they get an email saying "This is what your report was about, [keywords, temporal dates, author etc] do you want to amend these? Then tell me the address so that others can find it.". Automated data extraction, poking, prodding, chivying.

This is getting too deeply into the mechanics of the "how" to be counted as part of the vision.

Comment by Derek Scuffell posted on

Andrew, thank you for your thoughts on this and a small window onto the progress you are making in this critical area for UK farming and environment. Your point that meta-data “helps people find and share our data and information and to understand if it meets their needs”, is well made. The scope of people could be extended beyond people (as data consumers), as it is inevitable that the UK will have to harness artificial intelligence capabilities to have a more significant positive impact on UK productivity and environmental stewardship. Exploiting AI well will be possible when our farming and environment data are; captured, managed and shared under FAIR data principles. The FAIR data principles of ensuring data are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable, published first in Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 provide an elegant means for organisations to ensure that their data become enduring assets that capture value for stakeholders. Good use of meta-data is one of the battering rams to achieving this, and treating meta-data as first-class is an essential responsibility for data practitioners.

The “I” in FAIR is frequently overlooked or swept away by thinking that alignment with standards solves the challenge. However, as you point out, in a landscape that has abundant standards to choose from, it isn’t easy to know where to place your bet. The key to solving this is to use meta-data to define the meaning of the data (its semantics). When vocabularies define not just reference codes but also their meaning, they become assets that can connect datasets, regardless of the reference vocabularies those datasets have used. Doing this will ensure that published datasets are ultimately connectable to other data in the organisation and beyond.

An unequalled approach to creating and publishing meta-data, that described the meaning of data, is to use the Resource Description Framework (RDF). As RDF is a W3C standard, it remains vendor and technology agnostic, allowing the data (and meta-data) to be serialised in any desired format. I think that work the Environment Agency and the Food Standards Agency have already carried out to model vocabularies using RDF sets a good example of the direction we should expect all government departments to take, with meta-data.

The Agrimetrics UK agritech centre has made advances using RDF to create the meta-data that joins agri-food datasets together. A data market place, where analysis-ready data sets, API calls and query endpoints allow data practitioners to access data along with its meta-data from a landscape of connected agri-food data. Querying such an agri-food knowledge graphs is only possible through the best quality meta-data, and a significant contribution to this will be meta-data created by DEFRA.

As someone who is a data practitioner in the agri-food domain, and keen to see an improvement in productivity and environmental outcomes in UK farming, I’m pleased to see organisations care about how their data can be connected to other data outside of their enterprise. Cross-organisation data connection is also something that the GODAN report, “A Global Data Ecosystem for Agriculture and Food” shows is vital for the world to meet the needs for safe, affordable and nutritious food.

And dare I say as a tax-payer I’d like to see as much co-operation as possible between government departments, industry and the UK agritech centres to ensure data interoperability.

Comment by Anthony Leonard posted on

I like that your object is to "start a conversation about how we do metadata." I have dabbled with the concepts of RDF for some time now, and there is no better way of consistently describing both the world, and its metadata. But I also have a lot of real world experience of trying to join up inconsistently defined data and models, in established APIs published by different worlds, or even different parts of the same organisation, that will not go away but are a world away from RDF. For this reason I am tending towards JSON-LD as providing a stepping stones in this direction. It has RDF compatibility for when you have a store that can help you do a graph query somewhere, with federation and inference too if you like. But it starts out at simply layering more rigorous definitions on top of existing JSON without breaking it, and that is already a win for the developers (who may have moved on) maintaining the data, as well as those far removed integrators trying to consume it. In this sense I agree with one of the editors of the JSON-LD spec when he writes in the comments section of an extremely candid article on this (though more nuanced than this quote suggests): "... just making the JSON properties map to URIs and giving a JSON object an identifier of some kind is enough. You don’t need RDF. That’s all you need to give the object universal meaning, everything else is icing on the cake." http://manu.sporny.org/2014/json-ld-origins-2/

Comment by David K posted on

This seems to be the main standard of meta data included structured data that is often generated for websites where crawlers like Google can understand the significance of the page. The inherent issue then becomes how to value meta data as it becomes increasingly popular to use over time.

I work at https://rankmehigher.co/ and we struggle to find the best times to use meta and structured data for different websites. Product descriptions use different mark up than local businesses. Then there is organisation, article, news, etc. However, the mark up appears to be important only in the search engine arena.